Strategies for dealing with Impostor Syndrome

“Even though your achievements clearly emanate from you, you feel oddly disconnected from them”

It is a common ache between accomplished people to feel like they are holding on to a terrible secret. While on the surface everything seems well and fine, on the inside, not everything is as good as it seems. People who deal with impostor syndrome somehow fail to internalize their accomplishments. Privately, some might believe their accomplishments to simply be a matter of luck, they got their position by merely being at the right place at the right time. They believe that they shouldn’t be where they are, they believe they are faking it. Sooner or later, they know people will reveal this truth, and this causes them to live in great anxiety—anxiety that they are not good enough, that they are not as perfect as other people see them.

Impostor syndrome is a psychological state in which the individual doubts his or her skills despite receiving the opposite evidence from outside.

In a person living with impostor syndrome, outside, positive feedback is quickly dismissed and explained away, while any negative feedback, no matter how small, is taken as a clear sign that they are not good enough and don't deserve to be there.

But how can someone who is clearly so talented not see how good they are?

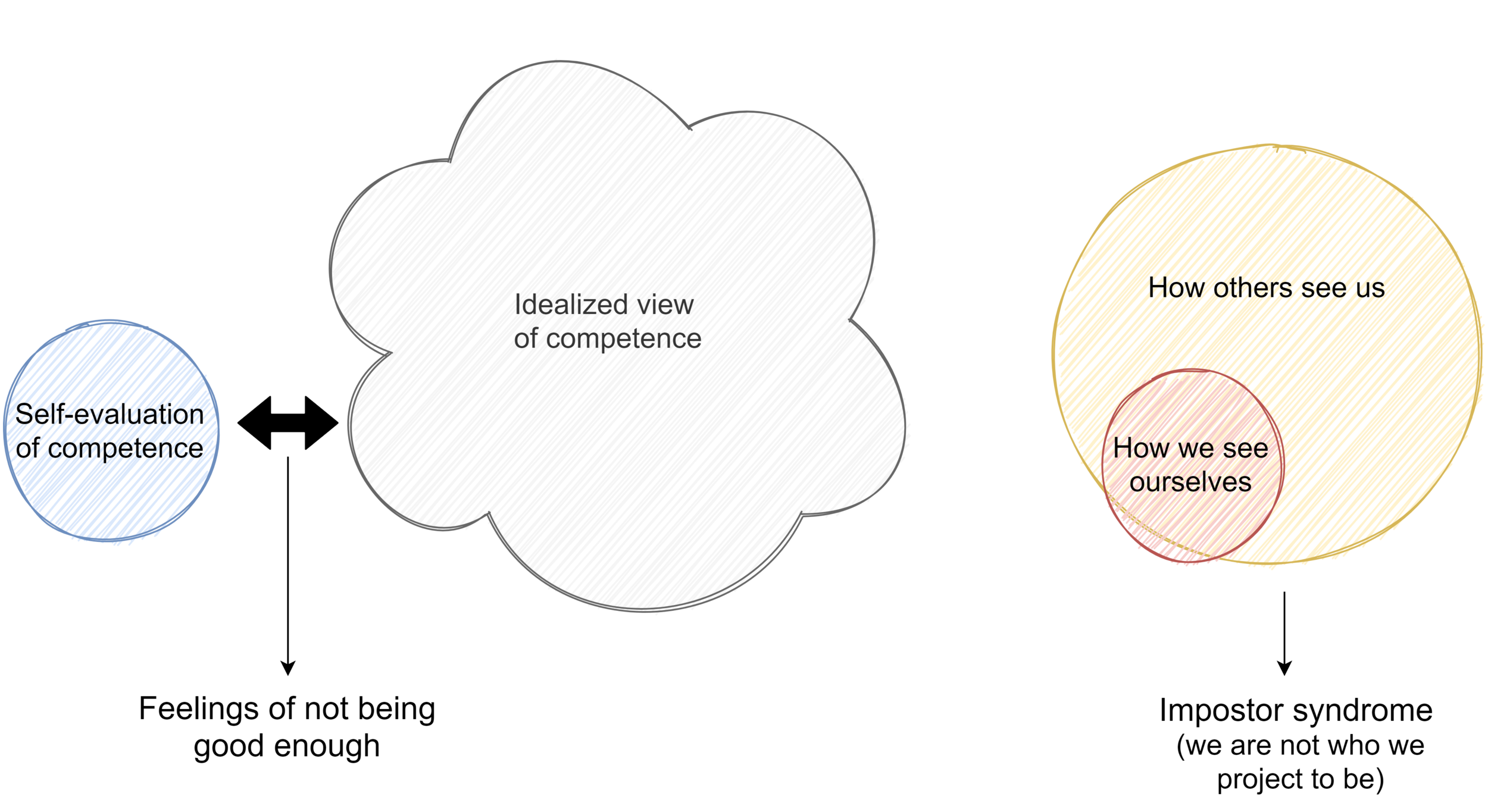

For the most part, at the center of our feelings of not being good enough is our own definition of competence and what a competent person looks like.

During our formative years, as we are climbing the ladder towards the top, we often tend to create and internalize an image of the kind of person that occupies the position we want to reach. This image is what we aspire to be—how we want to act, how confident we feel, how effortless we want to feel our accomplishments. Within reason, this image is never exactly accurate, but nevertheless, it comes to define how we represent competence in that specific position or role.

Once we reach that position though, we often end up being not as perfect as the image we created—we are still plagued by self-doubt and shortcomings. Maybe our work is not as good as we thought it should have been, maybe we don't know as much as we believed a person in our position should know. The discrepancy between the two images is what gives birth to the impostor syndrome. But notice that this discrepancy between who we are and who thought we should be is not dictated by outside feedback(other people often admire our work), rather, it is our belief in the skills we have that doesn't live up to our invented standard for excellence. In other words, we make up our lack of skill with a relative comparison that is often created only from our mind. Naturally, this discrepancy results in us feeling like we shouldn't be there, occupying a position that was clearly not destined for us.

Different types of idolizations fit different people depending on their field of choice and their natural inclinations. There are, however, some generalizations that seem to be present among impostors, you can see them as the more common types of idolizations and their consequences.

PERFECTIONISTS

The perfectionist measure of competence is flawlessness, perfectionists focus on how something is done.

For perfectionists, performance needs to be delivered 100% perfectly on every delivery to feel acceptable. Anything less than this self-imposed standard of perfection and you won't feel qualified for the job. When able to reach it, a perfect score or perfect work doesn't feel great, but simply "ok". Perfect work feels like how it should always be, which makes it merely satisfactory. Black and white thinking tends to dominate this view, if something isn't perfectly right, then it might as well be all wrong. Your standards are often higher than those of other people, you tend to do things yourself because you can't trust others to do them, with the loneliness and stress that comes with this habit.

Strategies for the perfectionist: learn to focus your perfectionists’ tendency on the work that is key, the one that is truly important. For most things, good enough and "done" work more than well.

NATURAL GENIUSES

Natural geniuses' measure of competence is on speed and easiness of execution, they focus on how and when things are done.

Natural geniuses follow the view of a fixed mindset. In a fixed mindset, intelligence is seen as a natural ability, not the byproduct of practice and experience over time. If the work doesn't come fast and easy, then you're clearly not up to the task. Learning is not part of the equation. Doing something quickly and easily on your first try means you're smart, struggling with anything means you're stupid. And when that happens, the impostor alarm starts pounding in your head.

Strategies for the natural geniuses: recognize that innate talent has little to do with your level of competence and achievement. Many smart people tend to live in their own shells because they are afraid of being seen struggling. The struggle is not a forced path for learning for those who are stupid, it is the only way. Shift your focus from your successes to the effort you put into a task. Difficult tasks make you grow, easy tasks inflate the ego.

EXPERTS

Experts measure of competence is on how much knowledge they have, how many skills they possess. They usually focus on quantity and how much they know.

A competent person, in the eyes of the expert, should know everything and have every answer. Experts are always looking for the next degree, the next credential, the next course. Only when they will reach the necessary expertise and feel qualified to start working and putting their knowledge to practice. But if we realize that with every answer we get 10 more questions to appear, we also realize that the path towards knowing everything is never over, and the impostor always lingers, waiting for that perfect knowledge to come, never feeling qualified.

Strategies for the experts: knowledge has practically no end, it's ok not to know. People don't hire you because you know everything, they hire people who know enough to get the job done. Realize that knowing everything is impossible, but in our imperfect knowledge, we can still make good use of what we already know. Put trust in what you already know.

RUGGED INDIVIDUALISTS

Rugged individualists' measure of competence lies in their ability to carry on the task on their shoulders and bring it to completion by themselves.

In this view, nobody is allowed to help you, to show that you have the skills necessary, you need to do it all by yourself. If you can't do it all by yourself, then you're clearly not competent for the job. Asking for help, even cooperating, is a sign of defeat and weakness. They go to great lengths to overwork themselves and show others that they can do it all alone. Only when 100% of their work is done by them they can take ownership of their achievements. They often are the types that value being independent and free from social obligations.

Strategies for the rugged individualists: competence sometimes means knowing how to collaborate with other people, using people's different skills to create the best results. Collaborating is part of the process, not a sign of failure. Knowing how to find the best person to solve your problem is one part of being competent, a sign of having social intelligence and interpersonal skills. Smart people tend to stay close to people who know more than they do. Smart people want to learn first, not show off. Asking for advice isn't a sign that you're stupid, but a sign that you want to learn. We always build on each other's strengths.

SUPERHEROES

Superheros measure competence by being perfect in every aspect of their lives, they have to be able to do all the things flawlessly. Might look similar to the perfectionist, but their focus isn't on how to do one thing perfectly to the last detail, but by being a role model in all the things. Perfect work, perfect diet, flawless exercise routine, perfect friend or spouse, while being a role model father or mother. This also includes doing all the favors your friends ask, working extra hours, taking care of the kids, eating healthy, and so on. If any of those roles become less than ideal all the others are seen as useless and your self-image crumbles like a castle of cards. With all these balls to juggle, something is going to fall eventually, and no wonder why, trying to do everything is a sure way of setting us up for failure in all of them. Superheroes have the habit of keeping on adding balls to the already too many they are juggling at this moment, making their lives look amazing from the outside, but miserable and stressful from the inside.

Strategies for the superheroes: to become decent at anything requires time and dedication, and that means that something somewhere has to take the hit. Compromises are part of life. Being less than exceptional in one area of your life doesn't make you less than a great human being.

Ultimately, there are admirable efforts in all of these searches for an unhealthy level of competence.

We all can have our own fears and insecurities, and shouldn't simply drop them, we want to recognize their value, and bring our expectations to a more realistic level. Perfectionists can be admirable for their high standards and great work outcome, but they should recognize that perfection is unreachable and forgive themselves for their shortcomings. As a natural genius, you are welcome to the pursuit of mastery of your craft, as long as you recognize that learning and struggle are part of the process. In experts, we admire their pursuit of knowledge, the search for answers to uncover the truth, but they should focus on the pursuit of knowledge rather than the knowledge itself—some answers could always remain elusive. Rugged individuals are admirable for their strength of character and autonomy in what they are doing, taking pride in knowing you can do anything alone if you really wanted to, but drop the idea that you must do everything that way. As a superhero, you can honor and admire your desire to be your best on multiple fronts, but recognize that doing everything isn't the answer to be perfect. Struggles and shortcomings make us all lovable humans.

There is a difference between knowing we could be better and thinking that we aren't good enough. This small shift in perspective can often make all the difference in the quality of our journey toward competence and the quantity of daily stress we create for ourselves.

The impostor syndrome is, like many other topics, more complicated than what a few lines can convey, but I hope this can help guide you in the right direction.

With the knowledge of the previous posts put together, I would like to cover why we tend to anticipate actions. Why does going backward help us move forward, why does going down help us go up, and how does this counterintuitive idea of going in the opposite direction make us move more efficiently?