LEARNING ANIMATION - A Journey on the Path to Mastery

INTRODUCTION

“Do not think that what is hard for you to master is humanly impossible; and if it is humanly possible, consider it to be within your reach”

Today’s topic will be about learning, more precisely, it’ll be about learning the learning process. While the lessons taken from it can be applied to any other craft, practice, or hobby, for the sake of this article I’ll try to focus on learning animation. I want to describe and investigate the learning process that takes place in mastering a craft, and hopefully help the readers understand better their own journey—where they are now, where they are going, and how to get there.

I never used stories from my private life to illustrate an idea in my articles, but that's how I would like to start this one, not because I believe that there is anything special in this story, on the contrary, I do it exactly because I believe it to be a very common experience something that you will be able to relate to. Furthermore, I think it introduces the questions answered through this article and it creates the perfect framework to start from. This story has nothing to do with animation, but it illustrates where I'm coming from.

When I was around the age of nine I used to spend my summers with my grandma at the coast on the sea of Italy. One night during those holidays, the circus came to this semi-touristic town to perform in a show, and we obviously went to see it. As the show went on, among the many incredible things they did, one thing got my attention above all—juggling. I cannot really be sure why that was the thing that caught my attention, since it didn't feel particularly special or the most flashy thing I saw that night, but somehow it “stuck”. Maybe it was simply that it looked the most "doable" of all the things they did.

In any case, armed with my best nine-year-old intentions I was set to master that one exact skill. The next day, I borrowed 3 tennis balls at the bar and went to work. I found a quiet place where I wouldn't be disturbed, disappearing for an hour or so a day (worrying my grandma who was searching for me), and started practicing. I didn't really have any teachers at hand to give me guidance, so my “training” became a lot of trial and error. During the first day, I couldn't manage to move beyond launching the first two balls in the air, so after a while, I decided to put the practice aside for the moment and enjoy the rest of my day.

To make a long story short, I went back to it in the next few days, getting a bit better each time, getting stuck in some plateaus, breaking out of them, getting stuck in new places. Lots of balls dropped, many mistakes, and some successes, until I finally managed to keep the juggling going somewhat indefinitely.

At the end of this whole "adventure", I was left somewhat wondering, why am I able to do this now? I clearly couldn't do it a couple of days ago, so what happened? It wasn't a matter of strength, my muscles didn't get any bigger or stronger. Maybe it was just what they called “muscle memory”, but do muscles have memory? I don't think so. But something must have changed inside of me because if it didn’t I cannot explain how I wasn't able to do it the first day, and how now I could be somewhat fluent. Something that was so awkward and clunky became so smooth and natural. I didn't know it at the time of course, but to answer these questions I would have to wait around 15 years.

In a way, what you are about to read in this article started back then, a long time ago. Now I want to answer that question, and add some, sharing with you at least a part of what I've learned so far.

No matter what the craft is, there are some big similarities in the learning process, how you learn to do one thing is how you learn to do anything. In the next chapters, we’ll develop a roadmap of where that learning process can lead us. This is my attempt to explore with you in a few lines a summary of what can take 20+ years of practice, in that magical journey from amateur to master.

THE LEARNING PROCESS: CONNECTING NEURONS

“Neuroplasticity is the property of the brain that enables it to change its own structure and functioning in response to activity and mental experience”

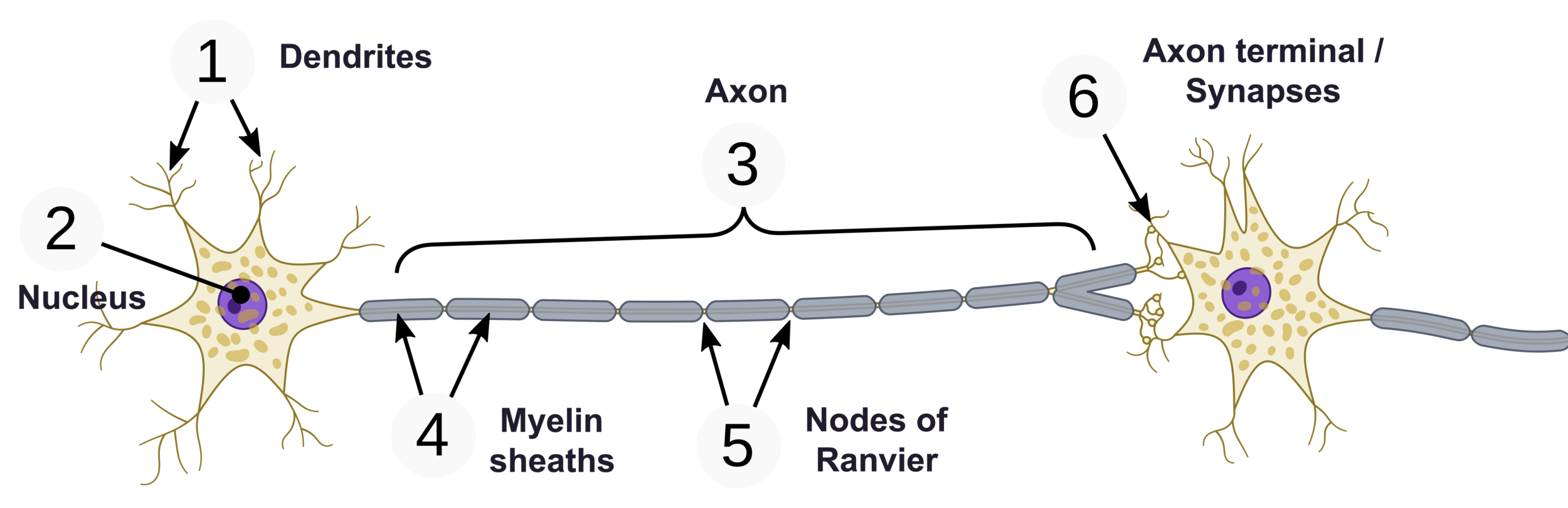

It is often wise to start understanding how the single elements work before we start looking at the big picture. In this case, we need to talk about the brain. Neurons are the basic units of the brain, and like any other cell in the body, they too have a life cycle that takes them from birth to growth, to death. Neurons are not static entities, they evolve and get replace continuously—our thoughts, our experiences, can change the structure of the brain itself over time. This is what is generally referred to as brain plasticity. But I'm getting ahead of myself, let's take a moment to dissect one of those neurons first and learn some terminology.

Generally speaking, the job of the neuron is to take the electrochemical stimulation for the previous neuron and pass it along to the ones it is branched to. Every neuron is formed by three main chunks: the dendrites, the nucleus, and the axon.

Dendrites are branch-like extensions of the neuron that receive the input from the other neurons connected to it. If the electric signal coming to the neuron is strong enough, it will be passed along the axon to the axon terminals that are connected to the dendrites of the neurons attached to them. There is an extra component of the neuron that, although technically not part of the neuron itself, is vital for communication—the synapse. The synapse is a small gap between the axon terminal of the previous neuron and the dendrite of the next one. When a certain amount of stimulation is received by the neuron, it sends an electrochemical signal down the axon and the axon terminals (the neuron activating is said to be "firing"), which is converted to chemical messengers released from the previous neuron that might (or might not) connect with the dendrites of the next neuron.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/5f/Simple_neuron_scheme.svg

There are two main types of signals a neuron can receive, excitatory and inhibitory. Generally speaking, excitatory signals will make the neuron more likely to fire, inhibitory signals, on the opposite, will make the neuron less likely to fire. On a macro scale, this dance, or symphony of activations played in our brain, with neurons firing in patterns, creates everything from our thoughts, our emotions, motor coordination, and so on… But all of this isn't static and set in stone.

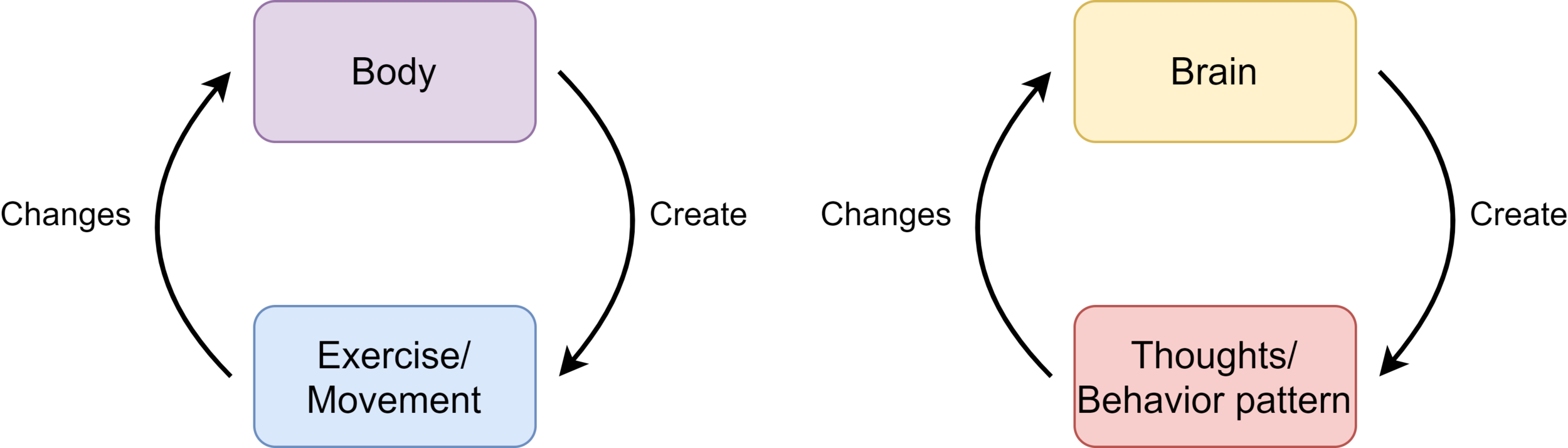

Just like the way our body is shaped influences the way we move, the way we move, over time, will shape and modify our body structure (that's why people exercise to become more flexible or stronger). The same principle is applied to the brain and mind, the way our brain is built will influence our thoughts, but repeating thought or behavioral patterns over time will also influence the way our brain is wired, making it more efficient at firing certain patterns in regard to others. Can you see where this is going?

Neurons that fire together, wire together. This is the base of neuroplasticity—when a certain pattern of neurons keep firing often in the same sequence those neurons grow closer, they grow stronger and more connections between their axon terminals and dendrites are formed, on top of that, the neuron itself becomes more efficient at sending signals down the axon. When we repeat something for a long enough period of time, the brain as a whole, and the neurons, in particular, reorganize themselves to become a lot more efficient at doing a particular task. Plasticity happens also in the synapses between neurons, where connections are made, strengthened, or weakened.

But plasticity has also its corollaries. First, it follows that neurons that fire apart, wire apart. Plasticity is competitive, and follows the rule of use it or lose it. To grow the stronger connections between neurons and the number of neurons themselves, they often take over other parts of the brain that are not used as often. As some circuits become old and unused, we lose them to make room for other ones that we might need more. Second, plasticity can create rigidity. As the connections between neurons become stronger and faster in their firing, it becomes harder and harder to take control and prevent that exact firing, and we become rigid in our ability to change. Once part of the circuit starts firing, it often goes all the way through, creating a shotgun effect that might not always be desirable. You might have had the experience of practicing something for a long time (let's call it pattern A), and when you are put in front of something that is similar to it, but not quite the same (pattern B), you can't help but move through pattern A instead. The strength of the connection of our synapses makes it harder to unlearn or rewire old behavior.

PRACTICE: THE APPRENTICESHIP PHASE

“Even the most motivated and intelligent student will advance more quickly under the tutelage of someone who knows the best order in which to learn things, who understands and can demonstrate the proper way to perform various skills, who can provide useful feedback, and who can devise practice activities designed to overcome particular weaknesses”

While the changes that occur in our body and brain are what allows us to do hard things with seeming ease and grace, we cannot directly access those changes. The body and brain will evolve only based on the stressors we present to it, not our wishful thinking. This process of stimulating our mind and/or body to purposefully selected stressors is what we call "practice", and it is ultimately how we can get better at what we are trying to master. When we enter a new learning adventure, we often start by practicing small and easy skills.

Every craft is composed of a certain number of macro and micro-skills that need to be mastered singularly for us to finally master the field itself. Learning to be patient and master each small piece will help us build a solid foundation and make the whole stronger. For example: learning to create an animation in body mechanics requires us being able to master timing and spacing first, ease-in and ease-out, and understanding gravity. With acting, we need to master mouth shapes, eye movements, facial expressions, and so on.

With classes and lectures we gather information, but it is through practice that we integrate that theory into an asset that we can rely upon.

Through trial and error, we learn to build a new skill, through purposeful repetition we consolidate and become more efficient at executing previously learned skills, while at the same time we polish the details and round the rough edges.

When we go through the first stages of learning anything, we first need to become aware of our deficiencies. As we learn about them we recognize where we often fall short, we learn where a different action is required from the current one, or where a new behavior needs to be implemented where now nothing is present. Depending on how complex the new skill is, the trial and error stage of learning by itself can take a good amount of time. After this stage, knowing how to consciously execute a skill doesn't mean we have mastered it. But, as we slowly keep on consciously forcing ourselves to apply the new skill, we transfer that explicit knowledge into implicit one. We do something without realizing we are doing it, we know how to do something, but we don't know how we do what we do.

Conscious competence becomes unconscious competence, we don’t have to think about how we do something, we just do it. Our minds, once focused on learning the new skill, becomes free to focus on something else, on the next skill to be mastered maybe, or on seeing the bigger picture.

Practice is the most effective way humans know to get better at things, but practice isn't just a number's game, as in, more isn't always better or helpful. Quality plays an important role in it. No matter how much effort we put in, some people end up remaining stuck in plateaus because of low-quality practice. While there is no shortcut to learning, learning how to practice effectively can be the difference between us getting better or remaining stuck in plateaus, unable to improve our skills despite the number of hours we are putting into it. In general, we can divide practice into three main categories:

Naïve practice: it can be summed up by "mindless repetition". In this type of practice people simply "show up" and "do things". People stuck in this type of practice want to improve, but their head is not focused on what they are doing. They are going through the motion, but without any real guidance, any real direction, any real conscious effort to make something different. People can spend years in this type of practice, always hoping to become better, but never being able to break through their current limits. While any type of practice can be useful in the very early stages of learning any skill (because any practice is still better than no practice), we will soon hit a plateau. We will eventually reach a point where we become decent, we will reach a point of "good enough", and when we do, our mind turns off during practice, we stop paying real attention to what we are doing, and we stop learning. This type of practice can become dangerous, because mindlessly repeating the same skill incorrectly not only will flatten progress but it will integrate incorrect habits, making it harder and harder to remove them in the future. Remember that our brain becomes more efficient at what it constantly repeats, if we keep exposing ourselves to bad habits, we will set ourselves back on the learning curve.

Purposeful practice: to escape the limbo of naïve practice we need to bring back some purpose to what we are doing. The core of purposeful practice is in being conscious and focused on improving. We practice with a specific goal in mind on what it is we need to improve at, and because of that, we often find ourselves out of our comfort zone. As we keep learning, we create challenging but obtainable goals, we forge a solid plan on how we will reach those goals, and we find a way to monitor our progress. With our improvement taking the center stage in our mind, we become creative in the way we try to break free of plateaus. We design exercises that work on our weaknesses, pushing through the discomfort that working on them might bring. But we do it with the incentive of knowing how much better we will be and the pleasure that often comes from gaining fluency in our skills. To make our practice purposeful, during the learning process we need to receive clear and directed feedback on our actions so that we know how to course-correct and adjust. No matter how much we love our craft, this type of practice is often laborious and not necessarily enjoyable, and this is for a couple of reasons. First, doing something new requires a lot of focus power, we cannot rely on our instincts and acquired behavior, and so we need to bring all our attention to what we are doing. Second, focusing on our weaknesses can make us feel vulnerable, while practicing our weak spots we are not as good as we used to be, and we see clearly our deficiencies in front of our eyes. It can almost feel like having taken a step back from when we were comfortably relying on our strengths to carry us. But this is often worth it in the end, as these efforts will give us the best results in the long run, working on our weaknesses will often make our strengths shine even more.

Deliberate practice: this is the gold standard for learning and mastering new skills. Purposeful practice encloses within itself the best an individual can really do on his own. While it is not impossible to master something in this way, learning everything by ourselves can lead to a lot of dead-ends, trial and error, frustrations, and loss of direction. Deliberate practice is, on the other hand, the combination of purposeful practice guided by the watchful eye of a skilled mentor, teacher, or coach. There is only so much we can learn on our own, and finding a mentor is still the best way we have to practice intelligently. A mentor is someone who's far along the path we want to walk, and he can help us save an enormous amount of time in many ways. Mentors can give us invaluable, personalized feedback on what we are doing and how we are doing, not only showing us where we fall short but also by giving us plans to correct ourselves that are tailored to our specific needs. They can make us aware of things we are not able to see in ourselves. They know where to focus our efforts and the traps to avoid along the path of learning. A mentor is there because he knows effective learning strategies, knows what works and what doesn’t, and what to focus on at any particular stage. A mentor can help us avoid dead-end goals, where a seemingly good fast way of improving can cause more harm than good later on. In short, the mentor knows where we are going and how to get there. Even though mentors don't provide shortcuts to the process, they make our journey more efficient and effective.

WHAT GETS IN THE WAY

The first stages of learning a skill probably put in front of us one of the biggest challenges in the learning process. Once we become fluent enough in any discipline we reach a tipping point where the action we take and the art itself become intrinsically rewarding: it becomes autotelic. From that point on, practice becomes easier to digest and more enjoyable, leading to practicing more often and gaining more skill, making what we are doing even more enjoyable in a series of accelerating loops. But to reach that point one thing above anything else can make or break our growth: our ability to deal with frustration. Frustration is a common part of learning, this is accentuated in the beginning stages because we cannot rely on previous skills, we don’t know if we are capable of doing what is required, and the process isn’t always enjoyable. Learning to deal with frustration is probably the most important skill to master in order to be able to get over the initial parts of the learning process. Here are some strategies to handle the emotions of getting stuck on a plateau:

Remember a time in the past when you went past a plateau and mastered a difficult skill. Having a sense of having mastered a difficult task can give you the necessary confidence to believe that you can do it again.

Focus on the process and not on results. Lots of things can influence the end result, focusing on what we can’t fully control is usually a recipe for increasing our level of stress and frustration.

Approach things from a different angle. Not all methods work with everybody, if you feel stuck, try a new, maybe completely different approach.

Take breaks. Your brain and body need time to assimilate all the new things you’ve learned, so give it time.

Celebrate small progress. Enjoy the journey you’re in, try not to focus only on the things you don’t have or the goals that were not reached.

FORGING A CAREER: THE CREATIVE/ACTIVE PHASE

“The study of numbers to leave numbers, or form to leave form”

We can think about the process of learning or mastering skills as being divided into three main stages.

First, we acquire new skills by entering the learning stage. Here, we are learning to put together the pieces. We want to achieve a certain result, but we either don’t know how to do that or, if we know how, we are simply not able to put that knowledge into practice. That’s why we need to incorporate new knowledge and behavior into our skillset. Our apprenticeship phase is mostly defined by the learning stage. Can you take the idea that is in your mind and execute it correctly? That is the goal of the learning stage.

Next on our way to mastering skills we enter the consolidation stage. Just because we managed to do something once doesn’t mean we have it under our belt. Can you take that level of quality and hit it consistently? Can you take those skills and apply them to different scenarios? Can you do it under pressure? While meeting deadlines? While also taking care of other tasks?

Consolidating a skill means taking something we can “do” and making it something we have mastered. This stage is often strengthened and practice as we enter the work world in our creative/active phase. During these years, we take our learned skills and really put them to the test until we know them from the inside out and they become part of our nervous system. At this stage, mindful (rather than mindless) repetition in different scenarios and on different stress levels is key.

Even at this stage, just because we know how to do something well it doesn’t mean we can stop practicing, much like you wouldn’t expect to get in shape once and remain that way. Remember that brain plasticity is competitive, and if you stop doing something, something more useful will take over that part of the brain. Now that we’ve mastered something, we enter the maintenance stage. We’ve put a lot of practice into learning and consolidating something, and we don’t want to forget it. This stage is not as intense as the learning one, but we still need to go back from time to time to revisit older and maybe not often used skills, or we might end up forgetting them. During our practice, it is useful to set up some time in our schedule to go back and revisit things we don’t get the opportunity to practice on a daily basis.

Moving through these stages, we leave behind the world of numbers and instructions and enter a world made of more complex ideas, intentions, intuitions, and abstractions.

THE EVOLUTION OF KNOWLEDGE

As we keep practicing smaller skills over a period of months and years what at the earlier stages was simple theoretical knowledge become practical skills. We move from knowing to knowing how, to forgetting how we know how to do something. With our basic skills becoming increasingly automatic and effortless, our mind is free from the cognitive load we’ve put it under until now. We are no longer trapped in managing the details of our actions and are free at this moment to start focusing on the big picture. In animation, this can mean moving past the simple techniques of timing, spacing, arcs, and so on, and focusing one's attention on a character's weight, his personality, his feelings and emotions, his intention, his current role in the storyline.

We take what once were single, isolated skills, and we blend them together to create chunks of information. Certain timings and spacings create weight. Combining certain types of body language and facial expressions create emotions. Creating emotions over time reveals a character’s personality. We start thinking in blocks and create patterns. If we try to take such big concepts too early in our development, the amount of information we would need to keep in mind would most likely overload our brain.

Our minds, once locked into focusing on solving a very specific problem, is now free to roam around, connecting and exploring all our different skills, adapting them fluently to the work we have in front of us. Our optimal focus shifts from hard and specific on a single task to soft and wide on a concept or feeling. During intense moments of concentration, we lose ourselves in the work, while practicing our craft becomes increasingly pleasant and our actions fluid. To get into this type of flow state we need to be somewhat relaxed and comfortable with ourselves, and if we are not, we can end up injuring the outcome of our work.

This transition from basic to complex knowledge often does not happen suddenly or consciously, rather, you notice at some point that things feel more natural and different, but you're not sure exactly when or how it happened. And this transition can only happen once we've internalized and mastered the basics.

Over the span of years, as we start mastering more complex skills and move higher and higher on the ladder of mastery, our internal, subjective experience of what by now can be considered a craft becomes more and more disconnected from the practical sides of it. Our thoughts become increasingly abstract, focused on feelings and intuitions, and our expertise becomes something that is hard to put into words. For instance, in creating a drawing we are not concerned anymore with the lines we make, instead, we might focus on creating something "elegant" or "harsh" or "raw". These abstract intentions and feelings are then shaped masterfully on the paper as our skills are up the task of putting to practice our intentions.

You can see an example of this by listening to Glen Keane talking about this sequence of the beast:

As we assimilate more and more skills in the form of tacit knowledge we tend to lose contact with the source of our skills. We develop a sense of intuition, or a feeling for what we are doing that precedes words. An example of having reached this level is most often revealed to us when we look at a certain work (ours or someone else's) and we have a feeling that something is not working and needs to be adjusted. Sometimes we might not immediately know what that is exactly, but it comes to us as a feeling, a flash of intuition. This sense of intuition is not inborn, but it is built from our practice, and it has a purpose. Our brain is one of the most metabolic organs of our body, and it’s always looking for ways to save energy. Consciously thinking about each and every step we make will waste too much brainpower. Because of this more direct, intuitive connection to what we are doing, our work feels more intimate and natural, guided by feelings and sensations rather than rules and instructions. With enough exposure, the tools we use become an integral part of our nervous system. The pencil becomes one with our hand and part of our body like it does the mouse and keyboard.

WHAT GETS IN THE WAY

With all these skills and knowledge under our belt we start playing around with ideas, and as we do that, we become increasingly creative and productive. We stop copying what others are doing, and we start creating. In this transition, we often leave our learning years behind and enter our active years, where we put all the things we’ve learned to practice, and if we are lucky, we end up making a living out of what we know. During this phase, our learning doesn’t stop, but since our livelihood depends on the quality of results we get, we might tend to lean on our strengths more and minimize our weaknesses. On top of that, new challenges are often added on top of our basic skills: deadlines, rush hours, quality standards, feelings of inferiority, interpersonal relationships, managing stress, and so on.

Since in the learning phase all our energies were focused on learning, mistakes were our friends and part of the process. If anything went wrong we were swiftly corrected and no harm was done. But suddenly, this dynamic can change. While before we were the ones paying for a service, now we are the ones on the receiving end of those payments, and this comes with side effects. Suddenly, we have a lot more to lose, and the pressure to perform rises. A new set of mental challenges and fears can sneak into our minds and injure our moment-to-moment quality of experience and the quality of our work.

Fear of failure can limit our focus and our ability to trust our intuition. We want to do good work, and to do good work we often try to put into it as much effort as we can, but this can often backfire. In order to feel that sense of struggle, we can end up putting too much effort into something we already know how to do well, ending up in us overthinking everything. Instead of accessing all our skills in a soft, relaxed focus, we revert back to the early learning stages and focus too much on one thing while ignoring everything else. In this way, our insecurities and lack of confidence can injure our intuition and our well-practiced abilities. While this type of concentrated focus is a necessary part of learning something new, it often hinders us in the moment of our performance. Learn to trust yourself and your previous practice. Relax a bit, and let the work flow through you. (“keep it simple, stupid!”)

Sometimes though, the opposite happens. As we become good at what we are doing, other people may start to recognize our work. Subconsciously, we internalize those compliments, and we start building an ego. As a result, we have an image to maintain, and we don’t want to fail or do anything that will destroy it. We stop taking risks, and because of that, we also stop learning. It’s hard to just “try something new” when your work and your image are at stake. When results and making the numbers is our first concern, delivering those results becomes our first goal, and because of that, we always fall back into what we know works. If we rely on this strategy too much or for too long, we stop trying new things, and we accidentally miss out on new opportunities for discovery and growth. Learning at this stage of the journey is a vulnerable act because while we want to send an image of confidence and strength, trying to learn is saying that we still don’t know things. But if we stop our learning process, over time we’ll see the people around us moving ahead while we remain stuck.

Conflicting short-term goals get in the way of long-term improvement. Namely: money, status, recognition. Priorities change as we get older, and while all these things can be great gifts on their own terms, they aren’t a part or substitutes for the learning process. Focusing too much on those as a means to display progress towards mastery can lead us further away from the learning process.

THE END POINT: MASTERY

“Perhaps we’ll never know how far the path can go, how much a human being can truly achieve, until we realize that the ultimate reward is not a gold medal but the path itself”

At the beginning stages of learning, we often approach the field as outsiders. The rules of the field feel awkward and clunky, we struggle to implement them. Even when we enjoy what we are learning, we can never quite connect to it, what we are learning feels like something that is outside of who we are. There is us sitting on one side of the table, and the thing we want to learn sitting on the other side.

As we master basic skills, we integrate them into our nervous system, changing our brain structure and the way our neurons are organized. Now, when we execute that basic skill, it doesn't feel like something coming from outside of us, like we are following rules or applying certain "techniques". Instead, it feels intuitive, it feels right, it feels natural. We repeat the same process over and over again with more complex, abstract skills, until they all feel natural, and the pencil we hold becomes an extension of our hand, the lines we draw, or the words we write an extension of our thinking. As we learn and perfect our craft, we learn things about ourselves also. Our character and personality—who we are— change and influence the learning process. But the opposite is true as well, learning something physically changes the brain, and as a consequence, it has an influence on how we think. After decades of exposure to certain patterns and stimuli, it's hard to separate who you are from what you do. For Leonardo da Vinci for example, drawing and thinking were the exact same thing. Drawing simply being an extension of his thinking, and a tool that helped him think.

When we learn something, this learning process doesn't just change what we know, it changes how we understand and look at the world. What we learn and the knowledge and skills we gather in our life color everything in our perception. What we know determines how we see, and the world will never look the same. Just as the language and culture we were born with is part of what determines our character, our personality, and how we understand things. Once you have the gift of knowledge and experience you cannot give them back.

To understand what I mean try this thought experiment: imagine you're showing a flower blossoming to a biologist, to an artist, and to a philosopher. All of them would look at the same exact flower, but they'll see completely different things. Their mind would naturally wander in very different directions from one another, and they would make connections with completely different ideas.

We see with our brains, not with our eyes. What we see out there cannot be separated from how we think and the structural organization our brain develops over time. Seeing it in this way, during the learning process the line that separates what we do from who we are slowly blurred as those two things keep affecting each other.

Our craft becomes so integrated into your system that it becomes the primary filter through which you see the world. Reaching that point of mastery is what makes people further down that path to have remarkable insights on creativity— if everything you do/see/hear is understood through your craft, everything becomes relevant and new connections are ready to be formed. The way somebody walks down the street can inspire a new dance move. A certain facial expression, or even a particular panorama, can inspire a new style of drawing. A story can inspire a new symphony. A person struggling can inspire the beginning of a new business. Everything becomes interconnected as we lose ourselves in what we do and develop a new baseline of seeing and understanding the world around us.

What we call mastery is the natural evolution of sustained, purposeful, and deliberate practice that extends over the span of decades. While many things can happen in this long journey, what keeps us going in this process is often an emotional quality rather than an intellectual one. What stops us from getting to the point of mastery usually isn’t a limitation of our brain or a lack of natural genius, but losing the spark that initiated it all, and the stopping of the learning process. That feeling of being alive and challenged that we had as amateurs can fade and leave us empty and uninterested in front of our work. Over that many years of practicing our craft many things can change. Our priorities shift, we might become numb to the daily routine of our work, we might become bitter and resentful to the reality of all the negative sides of our work we have to deal with on a daily basis. The joy of our work needs to be rekindled every now and then, we need to feel that sense of challenge and curiosity that initiated it all. Too often we see that spark getting lost.

Mastery isn't reaching a certain salary or status or having a lengthy curriculum. It's a learning process. People might think of masters in the form of status and recognition, and those things might come or not as we get better at it. But at its core mastery is about learning and skills, the same thing we do on the first day is the same thing we after 20 years—practice. For the most part, the mastery stage is mostly defined by the maintenance stage. Still, most of the people we call masters do on a daily basis is simply practicing the basics.

And we must keep learning and evolving if we want to stay relevant. Our field is constantly evolving and changing, styles change, technology evolves, the preference of the public shift. The moment we sit, thinking that we know all the answers is the moment we start our downfall. Inevitably, time will expose our lack of touch with the current times, our work becomes repetitive, old, and monotonous. When that happens, we become replaceable. We have to keep constantly adapting and remaining in contact with the public, ourselves, our own goals and motivations, and the current trends of the field itself.

It’s like being an explorer, many things can change and we can watch them come and go, we climb a mountain and go back down another, sometimes we stop, sometimes we go fast. In all these unpredictable changes in the road, the talent of the master lies in maintaining a beginner mind, where the joys of the journey come simply in taking the next step and getting better. To keep learning, to keep practicing, and keeping an open mind.

“The problem with all students, he said, is that they inevitably stop somewhere. They hear an idea and they hold on to it until it becomes dead; they want to flatter themselves that they know the truth. But true Zen never stops, never congeals into such truths. That is why everyone must constantly be pushed to the abyss, starting over and feeling their utter worthlessness as a student. Without suffering and doubts, the mind will come to rest on clichés and stay there, until the spirit dies as well”

“For the master, surrender means there are no experts. There are only learners”

“It is rarely a mysterious technique that drives us to the top, but rather a profound mastery of what may well be a basic skill set”

“Most people don’t have the patience to absorb their minds in the fine points and minutiae that are intrinsically part of their work. They are in a hurry to create effects and make a splash; they think in large brush strokes.

Their work inevitably reveals their lack of attention to detail - it doesn’t connect deeply with the public, and it feels flimsy”

“The best way to get past any barrier is to come at it from a different direction, which is one reason it is useful to work with a teacher or coach”

YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY:

Subjecting our work to other people's judgment is often one of the scariest things we can do. And yet we need it to grow, to learn, to improve our craft. What we don’t need, is to suffer because of it.

Bibliography and references

Beilock, Sian. Choke. Published: 2010.

Csíkszentmihályi, Mihály. Flow, The psychology of optimal experience. Published: 1990.

Doidge, Norman. The brain that changes itself. Published: 2007.

Doidge, Norman. The brain’s way of healing. Published: 2016.

Duckworth, Angela. Grit. Published: 2016.

Ericsson, K. Anders. Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise. Published: 2016.

Gallwey, W. Timothy. The inner game of tennis. Published: 1997.

Gallwey, W. Timothy. The inner game of work. Published: 2001.

Greene, Robert. Mastery. Published: 2012.

Herrigel, Eugen. Zen in the art of archery. Published: 1948.

Leonard, George. Mastery. Published: 1991.

Perry, John. Sport psychology: A complete introduction. Published: 2016.

Sterner, Thomas M. The Practicing Mind. Published: 2012.

Thompson, Hugh. Sullivan, Bob. Getting Unstuck. Published: 2014.

Waitzkin, Joshua. The art of learning. Published: 2007.

Walker, Matthew. Why we sleep. Published: 2017.

Pictures:

Juggling by Mochammad Algi

https://www.pexels.com/photo/crop-sportswoman-juggling-tennis-balls-on-meadow-4436470/

Mickey Mouse by Skitterphoto

https://www.pexels.com/photo/disney-mickey-mouse-standing-figurine-42415/

Artificial brain by Andrea Piacquadio

https://pixabay.com/illustrations/artificial-intelligence-brain-think-4389372/

Learning by ddimitrova

https://pixabay.com/photos/girl-father-portrait-family-1641215/

Photo Of Woman Studying Anatomy by RF._.studio

https://www.pexels.com/photo/photo-of-woman-studying-anatomy-3059750/

Persona Che Risolve La Distanza Dei Punti by Dids

https://www.pexels.com/it-it/foto/persona-che-risolve-la-distanza-dei-punti-2714073/

People Having Business Meeting Together by fauxels

https://www.pexels.com/photo/people-having-business-meeting-together-3183183/

Master Artist by AlLes

https://pixabay.com/photos/painter-artist-painting-palette-1454205/

Painting by Cottonbro

https://www.pexels.com/photo/a-serious-man-painting-on-a-white-cardboard-3779014/

Master and pupil by Andrea Piacquadio

https://www.pexels.com/photo/workers-handling-detail-by-pneumatic-tool-in-workshop-3846262/

Un étudiant De Sexe Masculin Diligent by cottonbro

https://www.pexels.com/fr-fr/photo/un-etudiant-de-sexe-masculin-diligent-lisant-un-livre-4861373/

Student doing homework at table at night by Kulik Stepan

https://www.pexels.com/photo/student-doing-homework-at-table-at-night-4384147/?utm_content=attributionCopyText&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=pexels

https://www.photojoiner.net/ for the photo edit

https://www.draw.io/ for the diagram

Today’s article will focus on understanding the anatomy of the wing that propels flight and the basics of aerodynamics that make flying a reality. We cover the different flight patterns and break down the three stages of flight: lift-off, flying, and landing. At the end, I've covered some curiosities about wing shapes and how they influence flight patterns.